| Timeless Nation |

11. WHERE EAST IS WEST

(The people, customs and folk art of the Transdanubian region)

Settlement, towns

Transdanubia — the region "Beyond the Danube" (in Hungarian: "Dunantul") is the area enclosed by the Danube and Drava rivers and the foothills of the Alps. It was once a province of the Roman Empire called Pannonia. The ruins of the Roman cities still attracted the Magyars who settled there after the VIth century: they often built their towns on the sites of Roman centers and used stones from Roman temples when building their cathedrals. The ornate sarcophagus of Saint Stephen was, for instance, made from an ancient Roman tombstone. This treatment compares interestingly with the Turks’ use of the sarcophagus. They threw the King’s body out of it and used it as horse-trough.

Transdanubia had the only "open frontier" of the former Hungarian Kingdom, which was enclosed by the Carpathians and the large rivers in the south. This geographic factor has brought about a stratification of regional characteristics among the Magyars born and educated in Transdanubia. They have always represented the search for western culture, Christianity (Catholicism), love of art, science and western technology. In politics they usually sought the ways of peaceful Cooperation and understanding as opposed to the fighting spirit of the Great Plains Magyars or to the astute and proudly independent spirit of the Transylvanians.

We shall mention some towns and regions of particular historic or cultural interest.

PECS, in the south of the region, the largest and probably the oldest town in Transdanubia. It had been a Celtic settlement before the Romans, who named it "Sopianae". Saint Stephen founded one of the first bishoprics here and the cathedral was built on the ruins of an earlier Christian basilica. The first Hungarian University was founded here in 1367. Near Pecs lies the old castle of Siklos with its gothic chapel and Renaissance ornaments. The castle-fort of Szigetvar bears witness to the heroic battle in 1566 when 1000 defenders held up Sultan Suleiman’s immense army for weeks. Mohacs on the Danube was the scene of the great military disaster in 1526.

Further to the north lies SZEKESFEHERVAR the old royal city. Saint Stephen called it Alba Regia and established his royal capital here. This city and its magnificent basilica remained the coronation and burial place for some 36 kings. Parliaments met here until the XIVth century. At the end of the 160 years of Turkish occupation nothing remained except the ruins of the old basilica, blown up by the Turks. They had ransacked the royal tombs and thrown out the bodies. To the north is the small town of Zsambek with its beautiful XIIIth century Romanesque abbey.

ESZTERGOM lies on gently rolling hills on the south bank of the Danube. In Chariemagne’s time it was the easternmost outpost of the Empire, called "Oster Ringum". This name was later magyarised in its present form. After the settlement of the country this city became the seat of the ruling chieftains and remained the Arpad kings’ administrative capital during the Middle Ages. The hill is crowned by the massive basilica, Hungary’s largest church, built in the XIXth century. The left aisle incorporates the so-called "Bakocz chapel", the only intact Renaissance structure in the country. The town itself contains the Christian Museum in the Primate’s Palace, rich in early works of Hungarian and Italian masters.

GYOR is situated on the banks of the Danube at the confluence of two smaller tributaries. Built on the site of Roman Arrabona, it became one of Saint Stephen’s early bishoprics. Among the few remaining treasures of the city is Saint Ladislas’ silver herma, an invaluable example of XIVth century Hungarian Gothic art. South of Gyor lies Pannonhalma, the Benedictine Arch-abbey, founded in the Xth century.

In the northwest of the region, near the historic fortress-town Komarom lies the small township KOCS. During the XVth century, the wheelwrights of the town. began to build a horse-drawn vehicle with steel spring-suspension. This "cart of Kocs" (pron. "coach") as the Hungarians called it ("kocsi szeker") soon became popular all over Europe. Practically all western languages borrowed the Hungarian town’s name to describe this new type of vehicle: "coach" ("Kutsche", "coche" etc.)

On the western border lies SOPRON, built on the site on an ancient Celtic centre. This is probably the only city in Hungary never destroyed by an invader. Near Sopron lies the town of Fertod-Eszterhaza with the sumptuous castle built by the Eszterhazy princes in the XVIIIth century. The great composer Haydn spent many years there as court musician. Around Kaposvar a characteristic folk-art style has remained in some villages. The Lebeny Benedictine abbey was built in Romanesque style in the XIIIth century.

In the southwest area lies the city of SZOMBATHELY, the Roman Sabaria. It had been an important Christian centre before the Hungarian settlement. Nearby, at Jak, stands the largest remaining Romanesque building in Hungary; the twintowered abbey built in 1256. North of Szombathely, near the border lies the town and castle of Koszeg where the Turks’ huge army was held up for a month by a small garrison of defenders who thus frustrated the entire Turkish campaign and saved Vienna (1532).

The Bakony Mountains lie north of the lake Balaton. The dense forests once used to serve as hiding places for the "betyar", the outlaws who play an eminent part in the folklore of this area. Zirc, in the heart of the region, is a Cistercian abbey, founded in 1182.

Veszprem, the picturesque (cultural and religious) centre of the Bakony region, was one of the first bishoprics founded by Saint Stephen.

In the Balaton Lake area one finds many places of cultural and folkloric interest. The Benedictine abbey of Tihany has preserved, in a Latin document (1055), the oldest recorded Magyar language words. The tomb of Endre I has remained intact in the crypt of the abbey. Keszthely, on the western shore of the lake, is the site of Europe’s first agricultural college.

Population, folk-culture regions

The population of Transdanubia is predominantly Magyar. After the settlement this region was inhabited by the most important tribes. The few remnants of autochthonous pre-settlement population were soon assimilated (some of them had already been related to the Magyars anyhow). The German settlers invited by the Arpad kings formed the only exception in this otherwise homogeneous population. The eastern half of the area suffered from the 150 years of Turkish occupation but the western part remained more or less undamaged.

Within the area, we can distinguish certain folk-culture regions, small districts with characteristic folk traditions. They are the results of certain geographical, social and historical conditions, which imposed isolation, or a certain type of occupation on the population.

South of Szombathely, near the Austrian border, is the area of about a hundred villages called GOCSEJ. This region, formerly isolated by swamps, has kept many old customs, songs, dances and artifacts connected with their mainly pastoral occupations, and a characteristic dialect.

A smaller group of villages near the western border is inhabited by the descendants of frontier guards, possibly Pechenegs (Besenyo: a race related to the Magyar), settled here in the IXth century as frontier guards. This occupation is remembered by the name of the area: "ORSEG ("Guards"). A watchtower-like superstructure on some houses is a reminder of the inhabitants’ original occupation.

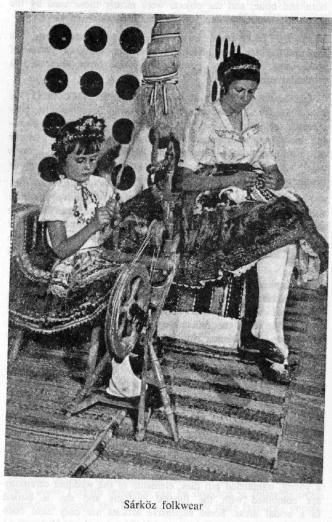

The SARKOZ district, near the Danube in the southeast, is a fertile area, inhabited by prosperous peasants who spend their surplus revenue on colorful costumes and artifacts —they could do worse with their money. We shall look at the Sarkoz folk art later in this chapter.

One region merits our closer attention: the "ORMANSAG", consisting of about forty villages situated on the plain stretching along the northern banks of the Drava river. The floods of the unruly river had created large marshy areas around the slightly elevated hills on which the villages were built. The peasants have developed a unique method of protection against the floods. From the earliest times they have built their houses on flat, heavy oak-beams placed on the surface instead of foundations dug into the ground. The house itself had solid timber walls with an adobe cover, held together by crossbeams parallel to the foundation beams. The outbuildings were built the same way. When the floods began to threaten the village, they placed rollers under the foundation beams, harnessed teams of oxen before the house and moved it to higher ground.

The most important — and tragic — social development began at the end of the XIXth century: the size of the arable land, which formed the property of the former serfs (liberated in 1848), was limited and there was no way of enlarging it. As the young peasants were unwilling to leave their village and marry elsewhere, the heads of the families began to impose the disastrous policy of "egyke" ("only child") upon the community, and this soon became the accepted social rule. It became customary. to have only one child per family and to prevent the birth of the others by abortion. When this single child grew up, he or she was married to another single child and the two family properties were united. Sometimes the "egyke" died before marriage. As a result, whole families died out and their properties were then bought up by new settlers, mainly Germans.

There is a moral in this somewhere for the advocates of "zero population growth"!

Another — happier — result of the villagers’ long isolation was the creation of a characteristic folk-culture. The families’ preoccupation with the happiness of their few children resulted in the encouragement of playful and artistic occupations for them. The village often rented a house (there was no shortage of vacant houses . . .) as a "playing house", a sort of "youth centre" where the children could play and the young adults could meet. Thus there was no need to go to another village to look for a spouse. Adolescents’ entertainments included such tempting games as "falling into a well": a lass or lad had to be "pulled out of the well" by the means of giving a kiss to the "rescuer" for each fathom given as the depth of the well. Consequently, Ormansag seemed to have the deepest wells in Hungary — and the least number of young people leaving their villages to marry elsewhere. There may be a lesson here too.

The period of isolation also created a treasure of folklore. Stories about the "betyars" are still popular, especially the ones about Patko Pista, who disappeared leaving behind a number of lovers and legends. As young lads in humorous disguises invade the play practical jokes on people (such as taking a coach to pieces and reassembling it in some inaccessible place). At Year’s Eve girls play guessing games, hoping to foretell the future, especially their future husband’s name. (They need not bother: their parents probably know it already…)

Many customs are connected d funerals: a sadly symbolic trait among these dying people. Professional mourners are engaged at funerals, who praise the dead in long, wailing songs. The relatives themselves are not supposed to show grief. After the funeral a lavish wake is held. The folk attire is characterized by white: older women and the mourners often wear white. These customs seem to be evocative of ancient Asiatic rituals, just as the custom of the movable house seems to be nomadic times. The predominance of white in folkwear has resulted in exceptionally high standards of cleanliness.

Folk art

Transdanubia, Hungary’s West, has produced folk art just as genuinely Magyar as the eastern regions, but this art shows a harmonious synthesis of the characteristic Magyar elements and of the effects of west: here Magyar East met Magyar West.

Western medieval (Gothic) art in geometrical patterns used in ornaments. The left its deep impression here, too, as everywhere the Magyar people. The Italian-Renaissance flood colors are found on folk dresses everywhere. The arcaded porches of the farmhouses and the herdsmen’s carvings both show Renaissance design. Because of the closeness of the Hapsburg-Catholic influence, the effect of the Baroque is more marked than elsewhere and can be seen in ornamental furniture carvings in the south. Even some Turkish influence can be detected in folkwear ornamentation, though the Turks were hardly their favourite people.

Some of the memorable forms of folk art are: CARVING, which used to be herdsmen’s art and flourished mainly in the Bakony region and in Gocsej. The materials were wood, horn and bone, and the objects were mostly those used by the shepherd: staffs, musical instruments, and vessels.

The POTTERY trade in some western towns dates from the times of the settlement and has followed the medieval system of guild-towns: the entire population of each town practiced a particular craft.

The Sarkoz district is the richest centre of DECORATIVE FOLKWEAR. Their special type of weaving (pillowslips, bedspreads, and tablecloths) covers the entire cloth with patterns showing birds, hearts, stars and geometrical patterns. The people are also accomplished embroiders, their main color scheme being white on black (the combination preferred by the equally aristocratic Matyos in Northern Hungary).

For their dresses the Sarkoz peasants use expensive material: brocade, cambric, silk. The most characteristic part of their dress is the fourfold silk shawl. The color scheme and shape of the headdress indicate the age and status of women. The shift (of Renaissance design) is made of very fine material called "szada".

At Kapuvar (in the northwest) even some men wear traditional costumes. The girls wear blouses instead of shifts. A shawl tied to the shoulders is worn under a velvet or silk blouse. The skirt (brocade or velvet) is folded in large pleats. The apron is iridescent silk with lace trim. Three to four bead strings are worn around the neck.

The originally Slovak village Buzsak is famous for its fine embroidered pillowslips.

Ornamental art is often used on festival occasions: with a symbolic meaning. In the Sarkoz, the "tree of life" — an artistic carving of a tree — is given to a young bride. This motif is of Mesopotamian origin. When a young woman dies, all her fine dresses are buried with her. At Csokoly the shroud and the funeral pillow show the woman’s age and status. When a young, unmarried girl dies, elements of the wedding ceremony are combined with the funeral customs and she is buried in a bridal dress. Some expensive articles are only used once a year, such as the "Christmas cloth" or the glazed dishes used at weddings.

Folk customs

Transdanubia has preserved a rich folklore in spite of the western influence and the Turkish wars. This miraculous survival of old tradition, going back to pagan times, can be understood if we remember the particularly strong Magyar character of the population of this region. This ancient folk element resisted German influence and Turkish oppression with the help of the natural environment, which favored the isolation and preservation of small settlements and cultural regions. We shall mention here some of the characteristic Transdanubian folk customs.

Minstrelsy ("regoles") still exists in the western counties. Around Christmas and New Year, boys or men form groups and go from house to house to sing their good wishes. (Cf. Chapter 6). The minstrels carry strange musical instruments: a stick with a chain and a pot covered with taut, thin skin with a long reed stuck in it. When drawn with a wet finger, this produces a strange, droning noise. Other instruments (bells etc.) are sometimes added. The "regos" often dress up as animals: bulls, stags and goats.

The charming custom of the Whitsun-Queen procession is undoubtedly of pagan origin. (Cf. Chapter 6). In some areas there is also a "Whitsun-King" election or rather competition among the lads for the title. The winner holds the title for two days with such privileges as free drinks and first dances at weddings and balls.

The Mohacs "buso" procession claims to celebrate the anniversary of a Hungarian victory somewhat overlooked by orthodox historians. It is said that, shortly after the defeat at Mohacs (1526), the population of the town hid in the swamps from the Turks. Eventually they came out of hiding wearing frightening masks of demons and monsters and chased the Turks out of their town. So today the people dress up at carnival time and parade in the streets wearing frightening masks.

There are many lighthearted customs at carnival time, such as the "mock-wedding" of Zala county, an elaborate comedy during which a boy and a girl, selected by their respective friends and wearing masks are "married" in a mock procession and ceremony. They remove their masks at the dance following the "wedding". Only then do they recognize each other. Though there is considerable verbal license during these games, no rough play is allowed.

Vintage festivals are popular around Lake Balaton, which is surrounded by world—famous vineyards. The process of gathering the grapes — "szuret" in Hungarian — became a word synonymous with good cheer and celebrations. Sumptuous meals, dancing and drinking conclude each day of the rather tiring work of grape harvesting.

| Timeless Nation |