| Timeless Nation |

14. THE OTHER HUNGARY

(Transylvania: its settlement, people, customs and folk art)

Settlement and history

This region of some 25,000 square miles is bounded by the rugged Carpathian mountains in the north-east and south. In the west a thickly forested group of mountains and hills (Bihar) separate it from the Great Plain, to which however several great river valleys provide easy access.

The Latin name, Transylvania, which appeared in the old Hungarian (Latin language) documents, means "Beyond the Forests" – beyond the Bihar forests as seen from Hungary proper. The Hungarian name, "Erdely", means "The Land Beyond the Forest,". The Rumanian language has no word for the land; their name Ardeal is a distortion of the Hunganan name.

The region is first mentioned in Roman sources. The rather nebulous "Dacian" empire was defeated by emperor Trajanus (105 AD) and held by the Romans until the end of the third century when they evacuated it completely. After them, nomadic tribes (Goths, Gepidae, Huns, Avars and Slavs) settled in the area. At the time of the Hungarian settlement in the lXth century, the remnants of these tribes and the Szekelys (of Hunnic or Avar-Magyar origin) populated the area which was, nominally at least, part of the crumbling Bulgarian empire.

In the Xth century, the area was allotted to two Hungarian tribes. The chiefs of these two tribes bore hereditary offices in the Hungarian tribal federation: the head of the southern tribe (probably "Keszi") was the second highest dignitary ("Gyula") of the nation. The Szekelys settled in the easternmost part and were given self-government as a tribe of frontier guards.

The powerful "Gyulas" of the southern tribe wished to emulate the head of the largest tribe, "Magyar" (the paramount chief of the Federation) and maintained independent cultural, political and religious contacts with Byzantium. The last "Gyula" actually rose against Saint Stephen's centralising attempts but he was defeated and the King broke the power of the tribal chief.

During the Middle Ages, Transylvania remained an integral part of the Hungarian Kingdom, but because of its relative isolation and strategic position it usually had a "governor" ("vajda") who co-ordinated the territory's administration and defence. During the XIIth century, Germans were settled in the remote areas and granted special privileges ("Saxons").

After the Turkish occupation of the centre of Hungary (1540) the region became separated from the rest of the state and gained a varying degree of independence. King John's son, John Sigismund, was the first Prince of Transylvania. This independence, forced upon the small country, maintained it as the bastion of the Hungarian nation during the 170 years of Turkish and German oppression.

After the failure of Prince Rakoczi's fight for freedom, the Habsburg regime ruled the region as a separate "grand-duchy" from Vienna. It did so against the protests of the Hungarians, who demanded the areas return to the mother country. The compromise of 1867 reunited Transylvania with the rest of Hungary.

The Trianon Peace Treaty (1920) gave the territory and adjoining districts to Rumania. Of the total population of 5.2 million, 2.8 million were Rumanians (Vlachs), the rest Hungarians, Szekelys and Germans. During the Second World War, the Second Vienna Award (handed down by Germany and Italy at Rumania's request), returned about 40% of the area to Hungary in 1940. During the rest of the War, the Soviet Union promised Transylvania to the country which changed sides first (both Hungary and Rumania were fighting on the German side). Rumania changed sides in 1944 and received Transylvania as her reward.

The Rumanian claim to Transylvania

Some Rumacian politicians claim that the Viaclis ofTransylvania are the descendants of the original Dacian and Roman population and thus claim Transylvania as their ancestral homeland.

The racial characteristics of the Dacians are unknown, but we know that the Romans evacuated Dacia in 271 A.D. when the Emperor (Aurelius) ordered the entire Roman garrison to withdraw from the untenable and distant province. Contemporary Roman historians report that all the Romans left Dacia, that no Roman settler remained and that no Roman had mingled with the local population. There is no mention of Dacian or Latin-speaking descendants of the Romans in Transylvania until 1224 when a Hungarian document first mentions Vlach shepherds, who began to move into the mountains and spoke a Latin-type language. As a matter of fact, the Rumanian language is partly Latin and partly Slavonic. German historians (not known for their Hungarian sympathies) place the Vlachs' original homeland in the centre of the Balkan peninsula where they lived under Roman rule and probably spoke a mixed Latin-Slavonic language. From there they gradually moved away, a large contingent reaching the Wallachian plain in the XIth century and then Transylvania in the XIIIth century. Under Turkish pressure (XVth-XVIth centuries) many more found refuge in Transylvania. Although the Vlachs were not numerous enough in the XVIth century to become one of the "three nations" of Transylvania (Magyars, Szekelys and Saxons), they received complete religious and cultural freedom under the tolerant rule of the Princes during Turkish times. They were, for instance, given the opportunity to print books in Rumanian. In fact, during the Turkish occupation of their home country (Wallachia), the only Rumanian-language books were printed in Transylvania.

During the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries the Hungarophobe Viennese administration encouraged Vlach immigration and at the same time oppressed the Magyars and Szekelys in Transylvania. After the Compromise of 1867, Transylvania was reunited with the rest of Hungary, but the neglect and complacency of the Hungarian administration resulted in the decrease of the Magyar and Szekely population as a result of their massive emigration to America. Thus by 1920 the area had a Viach population slightly in excess of the Hungarians.

Towns and districts with historic or cultural interest

Kolozsvar (Rumanian: Cluj", a distortion of the Hungarian name). This old city on the Szamos river used to be the capital during independence. It is the birthplace of King Matthias. The city still has many houses built in the typical "Transylvanian Flowery Renaissance" style. The Saint Michael Church is one of the few remaining Gothic cathedrals in the area. The city is the see of the Unitarian bishop of Transylvania. The Unitarian Church was founded by a Transylvanian Protestant preacher and is known only in the United States outside its country of origin.

Szamosujvar, north of Kolozsvar, is the centre of the Armenian community. They were given asylum from the Turkish persecutions in the XVIIth century.

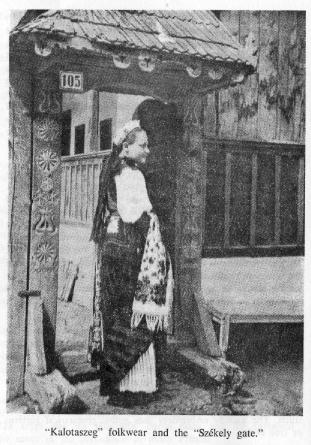

The Mezoseg region around Kolozsvar is an interesting Hungarian folklore region with characteristic art and customs. So is the larger Kalotaszeg district between Kolozsvar and the Bihar mountains, which consists of about 40 villages. The Magyar population of this region has preserved its customs, folk art and architecture, as well as magnificent folkwear to the present day.

At Keresd, south-east of Kolozsvar, the first books were printed in Transylvania in 1473. The town of Torda was often host to the Transylvanian Diet.

Torocko, near Torda, possesses the most sumptuous of all Magyar folk costumes, including some elements of Rhineland folk art borrowed from the neighbouring German settlers. Nearby, the gold-mining region in the Aranyos River Valley used to be the centre of the gold and silversmith industry.

Gyulafehervar on the Maros river, a former Roman centre, used to be the capital of the Magyar tribe of the "Gyula". Its first cathedral was built in the Xth century in Byzantian style. The crypt was the Hunyadis' burial place and the cathedral the scene of the coronation of many Princes.

The eastemmost districts are the traditional homeland of the Szekelys. The largest city is Marosvasarhely with its fascinating "Szekely Museum" and Library. Csiksomlyo is the pilgrimage centre of the Catholics among the Szekelys. The "Csangos" who live in seven villages in Rumanian Moldavia and Bukovina are Szekelys who migrated there in the XVIIIth century. There are today about one million Szekelys and Csangos.

Folk art and crafts

Transylvania is the only area where Magyar folk architecture is still found in its original form. Larger structures (churches) often combine stone foundations and walls with timber-roof superstructures. Separate timber bell-towers were added to the castles and churches. The timber constructions had to be renewed every two to three centuries but the renovators retained the original style (usually Gothic) of the building: The interior of many churches, especially in the Kalotaszeg area, presents elaborately carved, wood-inlay ceilings, pulpits and pews. The interior ornamentation is usually "Flowery Transylvanian" (Renaissance).

The entrance to the Kalotaszeg or Szekeiy house is usually through an ornamental wooden gate, shingle-capped, carved, coloured or painted, with high side posts. These are called the "szekelykapu (Szekely gate). In Szekely regions the gates are more elaborate; the carved columns are ornamented with flower motifs, allegorical, mythical figures and runic writing. Among the flower-motifs the tulip and rose are the most frequent. They are reminiscent of old pagan symbolism the tulip represents the male principle, the rose the feminine symbol. Another unique custom in Szekelyland is the use of the carved wooden headboards in cemeteries: these are called kopjafa (lance-tip). The inscriptions are often humorous.

We find some special types of weaving in the Kalotaszeg region. The Szekelys weave frieze-cloth for their trousers and coats. Their best-known product is the Szekely-rug", made of goat's or sheep's wool, richly patterned. Kalotaszeg is the home of the richest embroidery; some of it has free designs and patterns traced by skilled "writing women" (designers). Torocko produces a most elegant embroidery, finished in satin stitch. The Szekely embroidery uses gothic geometrical patterns or free design.

In the Kalotaszeg and Szeky areas even men wear folk-costumes on solemn occasions. They usually wear tight breeches of home-made frieze and in winter sheepskin vests or jackets (called "kodmon") and boots. The colour scheme is grey and black-white.

Women costumes are, of course, more colourful. Young girls wear colourful headgear ("parta") and the dresses are embellished with embroidery and woven ornamentation. The shirts, skirts and aprons are long. The skirt, called "muszuly" –often has one or two corners tucked in at the waist, displaying the colourful lining of the shift. The skirt is always covered with an embroidered silk or satin apron. Torocko girls wear strings of beads around the neck to complement their lavish costumes. The Szekelys, the poorest and most practical of these groups, wear simpler, more sombre dresses, with the red and white colours dominating.

Some folk customs

The old customs connected with the collective spinning of the flax-yarns in the spinneries have survived in the mountainous areas until the present day.

In the Szekely villages, the families rent a house where the women and girls perform the tedious task of spinning during the long winter evenings. There, with the aid of the village lads, they enliven their work with songs, story-telling, games and occasional dances: This arrangement has made the spinnery into a pleasant centre of village social life where work and play find their desirable combination, it provides the young with an opportunity to meet socially under the watchful (but understanding) eyes of their elders. The quality of the hemp-yarn may suffer but the romantic yarns spun may have a more lasting effect.

The girls arrive first and they begin their spinning at once as each of them is expected to spin a certain quantity before the games may begin. Eventually the lads arrive, settle down near their respective "girl-friends" (a relationship taken rather seriously) and try to distract the girls with singing and storytelling. If a girl drops her spindle, she has to ransom it in the "customary" way, with a kiss. On completion of the quota (of spinning, not of kissing), the games may begin. Some of these are pantomime-like ballets by which the boys show off before the girls. One such pantomime is the imitation of the usual farming tasks. The boys sing in choir and mime the actions of sowing, reaping, thrashing and selling their corn. Then they end by mimicking how the wives spend on drink the bard-earned price of the corn.

The boys may sing then the "Bachelors Song" in order to tease the girls, though boys entertaining the ideas of eternal bachelorhood (which the song advocates) would hardly entertain girls in the spinnery. This may be followed by games, such as the "selling of the girls", during which each girl is driven to a boy by two lads holding a knotted handkerchief. The songs sung on these occasions retain echoes of pagan love-chants used to. "charm" couples together. The mildly erotic games of the spinnery follow certain strict rules, guaranteed by the presence of the parents. They have learned to tolerate these games and thus make it unnecessary for young people to seek secret meetings out of the sight of their elders (or so the parents hope, anyhow).

The ancient custom of kalaka is unique among the Szekelys. It consists of mutual, collective help with hard, tedious tasks, to be rendered by each member of the community to each other member. House-building, well-drilling, ploughing and harvesting may be expedited by this system – invented by the Szekelys a thousand years before the birth of socialism. Widows and elderly people receive these services without the obligation of reciprocation; the others are expected to pay with equivalent work. Winter tasks, such as corn-husking and spinning are always performed this way.

The Szekelys' thousand-year-old role as frontier guards has made them into a proud race of battlers. Today they fight the elements of their rugged country, poverty and constant pressure on their national identity from the Rumanian state. Their history has turned them into expert "survivors": a self-reliant people with a devastating sense of humour, unlimited faith in their ability, a deeply emotional love of their language and sincere Christianity. Their rough pastoral occupations have made them into excellent handymen, skilled tradesmen and good businessmen (this last quality separates them from the "ordinary Magyars"). Their wives are resourceful and they rule their families with firmness and faith. Their exuberant husbands need a good measure. of discipline, which they accept from their wives – but from no one else on earth.

| Timeless Nation |