| Timeless Nation |

18. "HERE YOU MUST LIVE AND DIE..."

(The life, customs and art of the people of the Great Plain)

Towns and settlement areas

The "Great Plain" is not large by Australian standards: only some 30,000 square miles, but for the land-locked Magyars, surrounded by foreign, often hostile nations, the uninterrupted vistas create the illusion of unimpeded freedom. "My spirit soars, from chains released, when I behold the unhorizoned plain …" said the poet Petofi.

This area lies between the Danube river and the northern and eastern foothills of the Carpathians. It is cut into half by the Tisza river. The Treaty of Trianon has allotted the southern districts to Yugoslavia and the eastern fringes to Rumania.

Debrecen is the cultural and economic centre of the area east of the Tisza and the spiritual centre of Hungarian Protestantism. This town played an interesting role during the Turkish occupation. Situated on the crossroads of the three divided parts of Hungary, the town managed to retain some degree of independence by skilfully manoeuvring between the warring powers, paying taxes to all when this was necessary. The town fathers peasants and burgesses with remarkable commonsense and will to survive – made their town a refuge for the population of the nearby smaller towns and villages plundered by the Germans and Turks. Their numbers were thus swelled and reached a size, which had to be respected by the marauders.

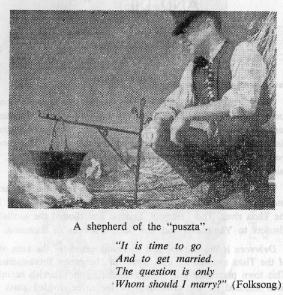

The Hortobagy is a grassy plain between Debrecen and the Tisza. Until recently it was a semi-arid area, called the "puszta" (desert). For centuries, the "puszta" represented, for the foreigner, the genuine "Magyar" atmosphere and the primitive lifestyle of the semi-nomadic herdsmen ("csikos") and outlaws ("betyars"), tbe proverbial "Magyar" way of life. This myth, born in the imagination of the XVIIIth century German travellers, was gleefully propagated by the Viennese rulers of Hungary and gullibly supported by the songwriters of Budapest (who sweetened it, of course, with romantic "gypsy" music). Irrigation and artificial fertillsation have now made this area fertile again and only a few "reservations" remain where the "csikos" perform remarkable feats of horsemanship for the benefit of tourists.

Kecskemet is a sprawling town between the Danube and the Tisza, situated in a region ideal for fruit-growing. During the Turkish occupation, this town – in the centre of the Turkish occupation area – remained relatively unharmed because the astute town-leaders managed to make the town a "Sultans fief". This assured its protection against plundering troops at the cost of enormous collective taxes paid to the Sultan. Other large towns (Szeged etc.) followed Kecskemet's example, protecting a considerable number of refugees, mostly peasants.

The city is Zoltan Kodaly's birthplace and the fine "Kodaly Music School", the prototype of scores of music schools, preserves his memory.

Large areas around Kecskemet are settled by scattered farmsteads, called "tanya". The "Bugac" "puszta" is a grazing area among barren dunes with some relics of primitive agriculture of the past (sweep-wells with their tall upright and cross-beams). It has a "romantic" reputation similar to that of Hortobagy.

Szeged, on the banks of the Tisza in the south, is well-known for its "Votive Church" (in memory of the 1879 flood), which forms a majestic background to an open-air theatre with 7,000 seats. The rich alluvial soil around the town produces the famous "paprika" (red pepper or capsicum) rich in Vitamin C (the study of which earned professor Szentgyorgyi his Nobel Prize).

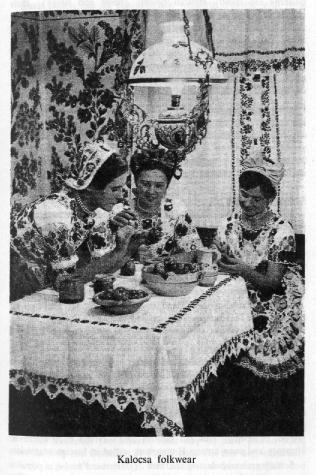

Kalocsa, near the Danube, was one of the original archbishoprics founded by Saint Stephen. Two of the archbishops. died on the battlefield commanding Hungarian armies. The peasants of the neighbouring villages have enjoyed great prosperity since the draining of the swamps at the beginning of the last century. They have used their affluence to develop luxurious folkwear and decorative artifacts.

Certain regions were already settled by non-Magyar ethnic groups before the Turkish occupation. Such a region is the Kunsag (Cumania) in the north. The ancestors of the Cumanians were eastem nomads (related to the Magyars), when they fled to Hungary in the XIIlth century before the Mongol onslaught. They were given refuge and have since completely assimilated into the Hungarian population.

The Jaszsag is a neighbouring area populated by the descendants of the "Jasz" (Yazygs), a people of Caucasian (possibly Iranian) origin. They came to Hungary at the same time as the Cumanians and integrated the same way.

The Hajdudg around Debrecen is named after the "Hajdus", who were Magyar cattle drovers, then, during the Turkish wars, foot-soldiers. In recognition of their gallant service, Prince Istvan Bocskai of Transylvania gave them special privileges and resettled them in this area.

The people and their art

The Great Plain is the most typically Magyar region of the Carpathian basin. Arpad's Magyars settled here first and in Transdanubia. Their descendants constitute the hardy peasant stock, which has survived a thousand years of floods, droughts, wars, pillage and destruction. Their destiny is best described by the words of one of the Hungarian national anthems: "Here you must live and die.

The peasant culture of the Plain is remarkably uniform as the development of large market towns and easy communication have prevented the formation of specific regional cultures.

History left its mark on the art of the people here. The inheritance of pre-Christian art still lives in certain ornamental patterns on carved objects. Asian motifs are sometimes found in folk-costume decorations, such as the patterns of Iranian inspiration in the Jasz region. The Renaissance culture left its mark on costume decoration. Turkish influence was also rather strong: gaudy ornamental patterns were introduced by Turkish craftsmen.

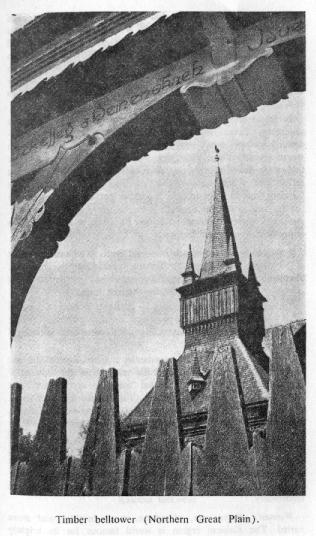

In this treeless area the main building material used to be reinforced adobe. Timber structures are found in the north-eastern wooded areas only, around the town of Nyiregyhaza, where several villages have fine timber belltowers with steeples topped by four little turrets. Woodcarving has been an ancient art in the Nyiregyhaza district, the best example being the Calvinist church at Nyirbator. Furniture carvings often preserve the religious medieval inspiration on the hewn (bridal) chests. Around Kalocsa, women paint the furniture and walls with improvised, gay flower designs.

Leatherwork and horn-carving had been the favourite craft of the nomadic horsemen before their settlement in Hungary. Shepherds and others connected with animal husbandry have kept this ancient art alive till the present times.

The Plain is a thirsty country – drinking vessels of various shapes, mugs, pitchers and jugs are popular artifacts. During the Middle Ages potters settled in special towns and specialised in certain types of pottery.

The cold winters of the continental climate suggest the use of hides and sheepskin as the basic material of the shepherds outer clothing. Short jackets, called kodmon" or "bekecs", are worn by men as well as women. The shepherds' thick coat, called "suba" is made of the skins of long-woolled sheep. The wool is left in its natural state whilst the skin side is often ornamented with applique embroidery made by the men. It protects the wearer against the extremes of the Plain climate: in summer, with the wool outside, it protects him from the heat; in winter the wool is inside to keep him warm. The "szur" is more elaborate: it is a frieze mantle or felt-coat with applied embroidery.

Womens, dresses are, of course, much brighter and more varied. The Kalocsa region is world famous for its brightly coloured, embroidered dresses. The colour schemes are gay (22 shades are used), as befits the sunny climate, and the decorative patterns are mostly stylized flowers (roses and tulips): their choice of colouring shows the effects of Renaissance taste. The white apron is trimmed with lace, the full skirt pleated and. many petticoats are worn under it. Coloured stockings and (red) slippers complete the dress. Unmarried girls wear a bright-coloured headdress ("parta") which they exchange for a bright-coloured kerchief after marriage. As they grow older the colours become sombre. Blue is the colour of the widows.

Embroidery in all shades is frequently applied not only to dresses but also to pillow slips, tablecloths and bedcovers. The designs often contain imaginative flower patterns or shapes resembling peacock-tails. In the Cumanian region homespun linen is decorated with applique homespun wool – a special art, the Cumanians' eastern inheritance.

Folk customs

Unlike folk music and poetry, customs do not change with the times. They perpetuate the original gestures and actions connected with some long-forgotten myth or rite of pagan times or some mystic, superstitious belief, which is no longer respected. The pantomime-like movements add colour and mystery to, festival occasions of the peasants life without any religious, or moral relevance.

The folk customs mentioned in this chapter are common to most regions in Hungary. The, central and open location of the Plain did not favour the development of characteristic regional folklore.

Easter is the first festival of spring and spring is the herald of love. Thus on Easter Monday the boys sprinkle water on the girls in a poetic well-wishing gesture. Usually scented water is used, except when things get out of hand with a few bucketfuls of fresh well-water "thrown in". The girls thank the boys for the gesture by offering them colourful painted eggs – an old pagan symbol of spring. This old custom has survived everywhere in Hungary and even among Hungarians settled in foreign countries.

Setting up maypoles on the first of May used to be a popular custom. The lad set up a tall pole with a large bunch of lilac (a native Hungarian flower) at the top in front of the house of his sweetheart. She indicated her acceptance by adding colourful ribbons to the decoration of the pole.

Each region has its characteristic wedding customs with local songs, dances, well-wishing and farewelling addresses in verse. The most moving scene is the brides farewell to her parents and their reply, often tinged with nostalgic childhood reminiscences and good peasant moral philosophy. Peasant weddings are elaborate and expensive affairs and it is no wonder that divorce is unknown among peasants: obviously no one can afford two weddings in a lifetime.

Harvest and vintage festivals are still popular in a country where so much depends on the year's harvest. At these festivals, a variety of slow and fast dances and songs expresses the various moods of the harvesters: the dignified ritual of thanks-giving alternates with the more temperamental celebration and tasting of the results of their toil: the fresh bread and the new wine.

The long continental winter is the period of light work around the house, rest and relaxation for the peasant. The winter calendar has many festival days connected with some ancient customs which have lost their original significance. The period before Christmas is also the right time to kill the fattened pigs, which provide many items of the farmers winter diet. The killing and preparing are usually done in a co-operative fashion with the help of the neighbours, who stay for the tasting of the fresh products.

The Christmas and Epiphany customs with their Christian religious character are discussed in Chapter 21.

On New Years Eve and on New Years Day the usual revelries are often seasoned with certain customs of pagan origin. Such a custom is the "kongo (sounding), a noisy procession. The noise is supposed to "frighten the darkness away": a relic of pagan Winter Solstice rites.

Name-days are welcome opportunities for family celebrations, especially in winter. Hungarians do not celebrate their birthdays, but they celebrate the Church feast day of their patron saint, whether they are Catholics or Protestants. On this day, especially if it is a parent's name-day, the family and friends gather and often sing one of the beautiful well-wishing folksongs and include the name of the person celebrated. By the same token, Catholic villages hold their annual fair ("bucsu") on the feast-day of the patron saint of their local church.

Constant social changes characterise the peasants' life today. Young men and girls flock to nearby towns or big cities to find employment, abandoning their ancient, peasant way of life. Thus much of the folk art, music and customs have ceased to be the spontaneous manifestation of the peasant soul. Instead it has become a carefully preserved and treasured cultural heritage. Folklore and folk art have, by their originality, inspired urban art, music and literature and by their very decline have helped to create a revival of folk-inspired art and music in Hungary.

| Timeless Nation |