| Timeless Nation |

19. REFORMS REVOLUTION REACTION

(Hungary’s history from 1800 to the Freedom War of 1848-49)

The awakening

When Napoleon reached the Hungarian frontier during his Austrian campaign (1809) he called on the Hungarians to rise against Austria. Remembering Louis XIV and his promises to Rakoczi, the Hungarians did nothing – and for once that was the right thing to do. They even fulfilled their obligations by supplying troops to the Emperor, Francis I (1792-1832) against Napoleon, though with considerably less enthusiasm than their ancestors did to help Maria Theresa – but then Francis lacked the remarkable attributes of his grandmother.

After Napoleon’s fall the Vienna Congress (1815) set up the Holy Alliance of the victorious powers with the aim of re-establishing the rule of absolutism in Europe. In Austria, which had become an Empire after the demise of the unlamented Holy Roman (German) Empire in 1804, Chancellor Metternich, the most forceful statesman of the time, ruled with an iron will on behalf of the feeble-minded Francis I.

It was during the years of this despotic government that, at long last, a number of young Hungarian nobles began to assess the condition of their nation. Slowly awakening after her "lost century", Hungary was a century behind the West and in need of urgent social, economic and constitutional reforms. The problems awaiting solution were immense:

(a) The language of the government, legislation and education was still either German or Latin.

(b) As a result of the Austrian resettlement policies the proportion of the non-Magyar nationalities rose to 50% of the total population of 12 million by 1820.

(c) Agricultural production – Hungary’s allotted role in the Empire suffered from old-fashioned methods, fluctuation of prices, inflation caused by the wars and neglect by absentee landlords.

(d) There were hardly any Magyar middle classes. The Austrian policy discouraged the creation of industry in Hungary and the rudimentary trade and commerce were almost exclusively in the bands of German-Austrian burghers and recent Jewish immigrants.

When the Diet was finally convoked in 1825, the rapidly increasing group of reformers was ready to suggest measures to solve these problems but the Viennese Imperial Council, headed by Metternich and Count Kolowrat, an avowed enemy of the Hungarians, refused to respond to their demands.

The first of these reformers was Count ISTVAN (STEPHEN) SZECHENYI (1791-1860), son of one of the few progressive Catholic aristocrats of Transdanubia. After a distinguished service with the imperial cavalry, young Szechenyi visited the western countries, (especially Great Britain), studying their democratic institutions, industry, economy, finances and agriculture. Returning to Hungary, he attended the 1825 Diet where he offered a large endowment toward the foundation of a National Academy of Sciences. Soon afterwards he summed up his suggestidus in a book entitled "Hitel" (Credit) (1830). He advocated equality of opportunity for all members of the nation, including serfs and nationalities, and blamed the complacent and reactionary nobility for the nation’s backwardness. He also advocated the solution of the social and economic problems before attacking the constitutional ones. A surprisingly large number of aristocrats and nobles welcomed his suggestions, however unpalatable they seemed to the conservatives.

At the Diet of 1832 another leading figure appeared, LAJOS (LOUIS) KOSSUTH (1802-1894). Scion of an old Protestant noble family of Upper Hungary, he was a lawyer by profession and possessed exceptional talents as an orator, writer and statesman. He immediately joined Szechenyi’s reform circle. Though they eventually became political opponents, Kossuth always maintained great respect for Szechenyi, whom he called "the greatest of Hungarians." Kossuth considered the nation’s political freedom and the constitutional reform as his prime target, while Szechenyi insisted that the nation must maintain its traditional ties with the dynasty and Austria and should carry out internal social and economic reforms first. During the subsequent Diets this difference in priorities separated Kossuth’s "Liberals" from Szechenyi’s "Moderates". The Vienna Council looked at Kossuth’s activities with increased suspicion and had him imprisoned for a while for breaches of the censorship laws (for having published a handwritten record of the Parliamentary proceedings).

After his release from prison, Kossuth became the political leader of the reformers while Szechenyi concentrated on promoting in a practical and unspectacular way the economic and cultural reforms he had suggested. He spent most of his considerable income in financing or initiating such projects as the development of steamship navigation, river regulation and flood mitigation schemes, the building the first suspension bridge between Pest and Buda over the Danube river and the publication of further works expounding his ideas.

The new Emperor-King, Ferdinand V (1835-1848) was an imbecile and had no say in the affairs of the Empire. The incessant demands of the Diet had finally some effect upon the Imperial Council and so the 1842 Diet was able to codify the use of Hungarian as the official language of the country. After 300 years the nation was allowed to use its own language in its own country

The peaceful "Revolution"

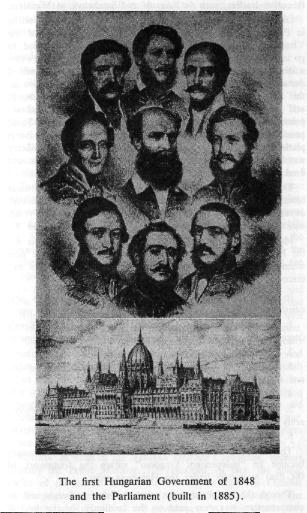

The Diet of 1847-48 was opened by the Emperor-King –in Hungarian. The first Habsburg in 300 years to use the language of his "loyal subjects" caused immense enthusiasm (and some merriment) among the assembled deputies. The Liberals, led by Kossuth in the Lower House and by Count Lajos Batthanyi in the Upper House, had practically unanimous support in both Houses. The Viennese Council began to show a more lenient attitude, especially after the fall of the French monarchy, which was followed by uprisings in several cities of the Empire –though not in Hungary (February 1848). Metternich resigned and a deputation of the Hungarian Parliament was received in Vienna by the Emperor (or rather by the Imperial Council, nicknamed "The Kamarilla"). The deputation submitted the demands of the nation and these demands were accepted by a much mellowed Council. A responsible government was appointed with Count Lajos Batthanyi as its Prime Minister and the other leaders, such as Kossuth and Szechenyi, as Ministers.

Dissatisfied with the progress of the Diet (which was meeting in Pozsony, on the Austrian border) and not knowing of the Vienna development, the youth of Pest and Buda decided to go into action on the 15th March, 1848. The poet Petofi wrote a stirring poem "Rise Hungarians" and read it to the assembled demonstrators. A crowd moved in a disciplined procession to the Buda Chancellery (the Office of the Governor-General) and presented their demands – the famous "12 Points" –printed, for the first time, without the censor’s permission. These points were almost word for word identical with the Liberal platform, which had just been accepted in Vienna. The military watched the demonstration with sympathy – not a shot was fired on this day.

Thus the people of the nation’s capital expressed, without bloodshed, its unanimous decision to abolish serfdom and accept sweeping reforms – an achievement which had cost the French nation hundreds of thousands of lives half a century before.

March the fifteenth, with its symbolic gesture has since remained the Hungarians’ greatest national day, the one day of the year when Hungarians all over the world forget their differences and discover what unites them: their love of freedom.

In April 1848 royal sanction was given to Hungary’s new constitution. The main innovations of this constitution were:

1. Establishment of a responsible government. The King’s decrees were only valid when countersigned by the government.

2. Re-establishment of the union with Transylvania.

3. Abolition of serfdom and equality for all before the law and equality of tax burdens.

4. Freedom of religion and of the press.

5. The establishment of a national guard (the "Honved" army).

6. Parliamentary elections by popular vote.

The relations with Austria remained unchanged:Hungary became an "independent kingdom" within the framework of tbe dual monarchy under the Habsburg ruler.

Though the feudal privileges were abolished overnight and no compensation was ever paid to the landlords for the loss of their serfs, there was no hostile reaction from the Hungarian nobility. It was obvious that the nobility’s much criticised "feudal attitude" had been motivated by lassitude and passivity rather than anti-social ideology.

Austrian intervention

The new Austrian Chancellor, Kolowrat, decided to neutralise the effects of the new constitution, "extorted, under revolutionary threats, from the feeble-minded Emperor" (as he put it). The Council roused the nationalities against the Magyars. The Magyar-hating Governor of Croatia, Colonel Jellasich, claimed that the new constitution endangered the traditional Croat freedom. So he demanded the restoration of centralised Viennese administration. The Serbs began to demand an independent Serbian state in the southern districts of Hungary. The Rumanians of Transylvania became the most willing weapons of the Viennese interference. They and the Serbs set out on a cruel and senseless campaign of pillage and murder against the defenceless Magyar population (which had no Magyar defence forces yet), while the Austrian garrisons stood by passively. In the north the Slovaks and the Ruthenes did not follow the example of the southern minorities. In fact thousands of them later joined the Hungarian "Honveds" in fighting the Austrians.

In June 1848 the murderous rampage of the Rumanians and Serbs moved the Hungarian Parliament to set up the National Defence Force. A National Defence Committee was formed with Kossuth as its chairman to co-ordinate the defence of the nation. By the end of September, the Imperial Council had practically repudiated the April constitution and ordered the Austrian and Croat troops to crush the Hungarian "rebellion" As a result of an unfortunate misunderstanding, the Austrian general Lamberg was killed in Pest. This inexcusable violence had far-reaching consequences: Prime Minister Batthanyi resigned and so did Szechenyi. This great man, horrified by the vision of a civil war, suffered a nervous breakdown and was taken to a Vienna asylum where he died by his own hand in 1860.

Kossuth, as head of the National Defence Committee, became virtually the Prime Minister. He remained, in fact, the actual leader of the nation during the ensuing struggle. In October the Emperor-King was made to sign a decree dissolving the Parliament and dismissing the government. As this decree was not countersigned by the government, it was not legal, of course. Austrian and Croat troops crossed into Transdanubia under Jellasich in September but this well-equipped regular army was defeated by a small force of hastily mobilised national guards under two young officers, Arthur Gorgey and Mor Perczel. The news of the defeat caused a shortlived uprising in Vienna (during which the hated war-minister, Latour, was lynched by the Austrian rebels).. So, in retaliation, the imperial commander, Windiscbgratz, launched a full-scale campaign against Hungary.

In December the Council forced the old Emperor, Ferdinand, to resign and his 18 year-old nephew Francis Joseph was declared Emperor. He was not even next in line of succession, the Hungarian government was not consulted and Francis Joseph was not crowned King of Hungary,

Thus Hungary was facing what amounted to external aggression by a nominal ruler imposed illegally by a coup d’etat.

The war of self-defence

The subsequent war has been called "War of Independence" or "Freedom War", even "Revolutionary War". At this stage it was none of these. Hungary did have her independence, guaranteed in the April constitution, similarly the freedom of a modern democratic society. No Hungarian leader wanted more in December 1848. Thus the subsequent armed conflict can be termed nothing but the defensive war of an attacked nation and its legal government against an external aggressor and its internal allies, the insurgent nationalities. For the same reason, many imperial officers –. Austrians and Germans – joined the newly organised "Honved" army.

The Diet, on Kossuth’s advice, appointed Arthur Gorgey commander-in-chief of the National Army. Gorgey, a former guards officer, a man with a cool scientific approach to military strategy, but also with great personal courage, was an excellent choice. On learning of Windischgratz’s attack he withdrew his untrained troops to the northern mountains. In Transylvania Kossuth appointed the brilliant Polish general, Joseph Bern, to restore order, which this admirable old man did, against overwhelming forces (Austrians . and Rumanian irregulars). He was equipped with little more than the admiration of his soldiers, a strategic intuition and determination.

The northern army of Gorgey, trained, hardened and rested, launched the victorious "spring campaign" in March 1849 and soon reached the Danube-bend, north of Budapest. It then turned to the north, defeating and outmanoeuving Windischgratz’s well-equipped regulars repeatedly. At the end of this whirlwind campaign, the imperials held only the fort of Buda and the frontier city of Pozsony. Windischgratz was dismissed in disgrace. In the meantime, the south of Hungary was pacified by Mor Perczel, a gifted civilian-general and the Serbian-born John Damjanich who, disgusted with the atrocities committed by his fellow nationals, joined the Hungarians and became one of their most successful generals. Bern was holding Transylvania: Hungary seemed to have defended herself successfully.

Independence, Russian intervention, defeat

On the 4th of March, 1849, Francis Joseph proclaimed the abolition of Hungary’s self-government. Kossuth decided to end Hungary’s constitutional vacuum and convened the Diet in Debrecen. On the 14th of April, 1849, the Diet declared Hungary’s complete independence, dethroned the Habsburg dynasty and elected Kossuth Regent. A new ministry was formed with Bertalan Szemere as the Prime Minister.

Whilst legally justified, this action came at the wrong time. The revolutions and uprisings of Europe had by then been defeated, except in Hungary. Moreover, unknown to the Hungarians, Austria had already asked for the Russians’ help to crush the Hungarian "rebellion". The Tsar obliged and dispatched 200,000 elite troops against Hungary.

On the government’s instructions Gorgey undertook the wasteful siege of Buda and took the strong fort in May. By that time, however, a newly organised Austrian army and fresh Russian troops were preparing for a new assault – a total force of 450,000 with 1,700 cannon, against the exhausted, under-equipped Honved army of 170,000 (with 450 cannon). Gorgey made several bold attempts at defeating the Austrians before the arrival of the Russians, once he led a cavalry charge himself and was gravely wounded. Eventually he had to withdraw before the joint Russian-Austrian forces. In August Kossuth realised that the war was lost and transferred all his powers to Gorgey, then left the country.

On the 13th of August, 1849 Gorgey, at the head of the remaining Honved troops, capitulated before the Russian cornmander. The fortress of Komarom under the brilliant young general Klapka, held out for another six weeks.

The sadistic Austrian general Haynau (nicknamed "the Hyena’ for his cruelty in Italy), was made Hungary’s military dictator to vent his wrath upon a defenceless people. He had 160 soldiers and civilians executed, among them 13 generals and ex-Prime Minister Batthanyi, and sentenced thousands to long prison terms. At the Tsar’s special request Gorgey was pardoned and interned in Austria.

| Timeless Nation |