| Timeless Nation |

22. GLORY WITHOUT POWER

(Hungarian history from 1849 to 1914)

Passive resistance and compromise

Though Hungary’s dictator, general Haynau, was dismissed in 1850, after a year of his reign of terror, the Viennese administration proceeded with its plans for a total absorption of Hungary into the Austrian Empire. The entire country was divided into districts administered directly from Vienna. This arrangement, aimed at the forced assimilation of the Magyars, angered the nationalities as well, as they lost even the limited cultural freedom they had enjoyed under Hungarian rule, against which they had so enthusiastically helped the Austrians.

Only a few of the 1848-49 political leaders dared to remain active in Hungary. The most eminent of these was the moderate and wise Francis Deak, minister in the first 1848 government. Helped by the leading writers and intellectuals of the nation, Deak urged the Magyars to fight for their freedom by peaceful, passive resistance.

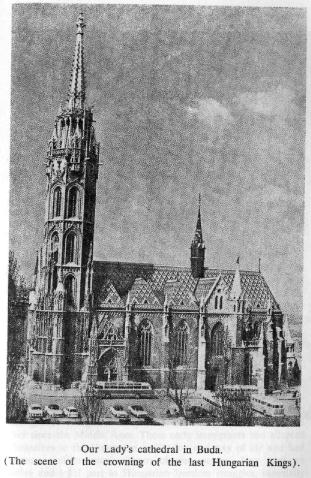

Thus the Viennese regime had to face the mounting dissatisfaction of the nationalities, the passive resistance of the Magyars and soon also the impact of disastrous military and political events in other parts of the empire. The successful uprising led by Garibaldi lost Italy for the Habsburgs. In order to appease the Hungarians, Vienna offered some concessions, but Deak and the other leaders insisted on complete acceptance of the 1848 April constitution (cf. chapter 20). When the short Austrian-Prussian war ended in disaster for Austria (1866), Vienna realised that the empire could not survive without the Hungarians’ co-operation. In 1867 the Emperor, Francis Joseph, accepted the entire I 848 April constitution and appointed a second responsible ministry under count Gyula Andrassy. Francis Joseph I and the Empress, Elizabeth were then solemnly crowned in Buda as King and Queen of Hungary.

The 1867 agreement of reconciliation between Austria and Hungary, called Compromise ("Kiegyezes"), re-established the dual state structure (cf. chapter 20). The sovereign states, Austria and Hungary, ruled by one hereditary Habsburg monarch, were to share three "common" departments: Foreign Affairs, Finance and Defence, but both states had their own defence forces (national guard) as well as a "common" army.

Lajos Kossuth and the emigration

After the collapse of the freedom struggle, Kossuth sought refuge abroad, accompanied by several political and military leaders. After a short stay in Turkey, he was invited to the United States by the government of that country. An American warship brought Kossuth and his fellow-refugees first to Britain, where he captivated his listeners with his English oratory. (He had learnt English in his Austrian prison). After a triumphal welcome in New York, the Hungarian statesman was invited to address a session of the U.S. House of Representatives (an honour only granted to one other foreign statesman, Winston Churchill). During his stay in America as the "nation’s guest" he delivered several hundred speeches in English. Thus he managed to make the fate, of his nation known to the western world.

Returning from the U.S., Kossuth lived in England, watching the European political scene and hoping that an opportunity would arise to launch another campaign for his country’s freedom. During these years he managed to gain world–wide sympathy for the oppressed Hungarian nation. General Klapka organised "Hungarian Legions" in Italy and during the Prussian-Austrian war a Hungarian legion was actively engaged against the Austrians. Though there were no real prospects of a revolution in Hungary, or of an armed intervention, the constant pressure of European and American public opinion maintained against Austrian oppression, and fomented by Kossuth’s activities, remained a real threat to Francis Joseph’s shaky empire and became a deciding factor in hastening the Austrian acquiescence.

After the Compromise – which he refused to accept –Kossuth withdrew from international politics. He objected to the Compromise because he believed that Hungary, tied to a doomed Austria which was led by ultra-conservative politicians, would eventually suffer the same fate: annihilation. This prophecy turned out to be tragically true. It was Austria’s bumbling diplomacy, which brought forth the War of 1914, causing Austria’s and with it Hungary’s – downfall.

The elderly Kossuth retired in Torino, Italy. In his writings he advocated the formation of a "Danubian Federation", a confederation of Central European nations from Poland to Greece, forming a block of united states between Russia and Germany These suggestions of the great political philosopher are wishfully remembered today as the only solution that could have prevented the horrors of two world wars.

Kossuth died in Torino, Italy, in 1894. Only then was allowed to return to the country of his birth. His remains were brought to Budapest and laid to rest there.

The Liberal governments

Prime Minister Andrassy resigned in 1871 to become the Monarchy’s Foreign Minister. Eventually, count Kalman Tisza formed the so-called "Liberal Party" which was to govern Hungary for the next 40 years. Tisza himself remained Prime Minister from 1875 to 1890.

The shortcomings of the Compromise all but nullified the concept of equality between Austria and Hungary. The important "common" portfolios of Foreign Affairs, Finance and Defence were managed almost entirely by the Emperor’s Austrian advisors and the ministers were Austrians most of the time. Soon, under Kossuth’s influence a number of Hungarian politicians began to feel dissatisfied with the 1867 Compromise. The representatives opposed to the spirit of 1867 called their group the "Independence Party". The members of this Parliamentary opposition presented a more or less emotional attitude toward the Compromise but their views on social and cultural matters differed little from those of the government. There was no party with a radical social program in the Hungarian Parliament during the last decades of the XIXth century.

The subsequent Liberal governments were headed by such Prime Ministers as the able economist Sandor Wekerle (1892-1895), the efficient administrator Kalman Szell (1899-1903) and the energetic count Jstv’n Tisza (1903–1905).

It was during this period, in 1896, that the nation celebrated the millenary of the occupation of the Carpathian basin by the Magyars of Arpad. The Hungarians celebrated their "Millenium" with great pomp and flourish, contemplating their glorious history, cultural, artistic and technical achievements with justifiable pride, but in their complacent euphoria they ignored the signs of the gathering storm which was to destroy their thousand-year-old kingdom in little more than two decades.

The problems of the "millenary" era

Three factors had contributed to the social problems of these decades in Hungary: the general European social atmosphere which caused upheavals in almost every country, the conservatism and complacency of the Hungarian ruling classes and the deficiencies of the Compromise.

The ‘Compromise had allotted to Hungary the role of agricultural provider, while Austria, with her industries (well established during Hungary’s ‘lost" XVlllth century), was to be the prosperous, industrial partner. As there were no tariff frontiers between the two states, Austrian industry had first claim on the cheap Hungarian produce, including Hungary’s considerable mineral wealth. The fledgling Hungarian secondary industry had the unenviable task of competing against the efficient Austrian factories. The ineptly managed, often foreign owned, unprofitable Hungarian industries could not assure decent living standards to their workers and soon created discontent among the urban proletariat. Besides, the raw materials and power sources were situated in the mountainous areas of Hungary, which were inhabited mainly by the national minorities. Thus the modest benefits of mining and industrial exploitation affected mostly the non-Magyar population. The Hungarian landed aristocracy made matters worse by preterring the gentlemanly comforts of their old-fashioned estates to the challenges of modern industrial ventures. Similarly, the poor Magyar peasants preferred the poverty of their ancestral villages to the uncertain prospects offered by the slowly developing urban industrial centres. The small landowners – the former lower nobility – were practically ruined by the cheap food prices and their inefficient production methods. So they flocked to the cities to increase the rapidly growing army of public servants – the only occupation worthy of a gentleman. Trade, commerce and the free professions were left to the Germans and Jews.

The ruined peasants and the urban workers, dissatisfied with their conditions, found the solution for their problems in emigration. Between 1890 and 1914 more than a million Magyars and other nationalities left Hungary for the haven of America. Like these social problems, the problems of the national minorities were largely ignored by the governments and leaders of the "millenary era". At the 1910 census, Hungary proper (without Croatia) had a population of about 18 million. 60% of these – about 11 million – were Magyars, the rest –7 million –. "minorities": Slovaks, Serbs, Rumanians, Germans and others. The ‘Nationalities Law" of 1868 granted equal rights to all citizens of Hungary, irrespective of nationality or religion. The official language of the central administration was Hungarian but the lower echelons (counties, municipalities, shires) accepted the use of the language of the national minorities of that area. Denominational schools were allowed to use the language of the supporting nationality. This meant practically unlimited primary and secondary education in the minority languages as in 1868 almost all such schools were denominational.

No European country gave more rights to its minorities at that time. Neither were the social conditions of the minorities harsher than those of the Magyars. In fact the number of landless Hungarian peasants was equal to the totai number of the Rumanian and Serbian minorities.

Thus the disagreements between Hungarians and the nationalities were not caused by legal, social or economic discrimination but solely by external political interference. After gaining their independence from the Turkish empire, Serbia (independent since 1844) and Rumania (independent since 1866) embarked upon an imperialistic policy of their own: both states made every effort to acquire the territories of Hungary inhabited (partly) by their fellow nationals who had migrated there in the previous centuries. To promote their aspirations, both states incited their brothers in Hungary to fight for their independence. On external instigation, the Serbs and Rumanians of Hungary protested against the dual Austrian-Magyar state-structure, demanded equal participation, rejected the equitable 1868 Nationalities Law and refused to co-operate with the Hungarian government in every way. Soon the Czechs – who were then still Austrian subjects without territorial autonomy – began to instigate the Slovaks of Northern Hungary in preparation of their planned "Czecho-Slovak" state.

The Hungarian leadership failed to see the master design behind this discontent and attributed it to the impetuosity of individual extremists. Sporadic emotional reactions by Magyar politician were of no help: they only provided more ammunition for the well-planned Rumanian-Serb-Czech campaigns.

The road to World War I

The heir to the Habsburg throne, Archduke Francis Ferdinand (successor to Crown Prince Rudolf, who died in 1889) took an active part in internal and external politics. He disapproved of the Hungarians’ "equal" role in the Monarchy and planned to re-establish a XVIIth century type of absolutistic, centralistic empire. In order to neutralise the Magyar influence he favoured the Slavs, especially the Czechs.

When in 1905 the Hungarian opposition, led by Kossuth’s son, Ferenc, toppled the Budapest government, Francis Joseph refused to appoint a Kossuth government. After a period of internal wrangling a coalition government was eventually formed under the former Liberal Premier, Sandor Wekerle. This coalition government was unable to carry out the promised reforms in the face of stiff Viennese resistance, inspired by the Magyar-hating Crown Prince. The government resigned and at the 1910 election the Liberal Party regained its absolute majority and formed a new government. At this election smaller opposition parties with radical social and cultural programmes began to appear on the Hungarian political scene. Some of these were the Catholic People’s Party (Christian Democrats), the Social Democrats, the Peasant Party and the Radical Party.

The foreign policy of the Monarchy was influenced by heavy-handed Austrian politicians and generals, who ignored the signs of the Monarchy’s decline and kept dreaming about a great Austrian Empire. In 1908 they decided to annex the provinces of Bosnia and Herczegovina, freed from the Turks. The Budapest Parliament protested against the annexation of the entirely Slav-populated territories.

The Balkan wars of 1912-1913 seemed to foreshadow the end of the long period of peace in the area, but only count lstvan Tisza, Prime Minister (for the second time) since 1913, heeded the warning. He wrested from the Parliament a much-needed defence appropriation and used stern methods to end the sterile obstruction of the opposition in order to introduce progressive legislation. It was too late: the modernisation of the antiquated Hungarian defence forces and of the archaic electoral laws had hardly begun when the storm broke . .

On June 28, 1914, the Crown Prince, Francis Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated in the capital of recently annexed Bosnia by a member of a Serbian secret society.

The balance of the "millenary" era

The unsolved social and minority questions were the main items on the debit side. Austrian pressure and foreign agitation, though real, do not entirely excuse the Hungarian leaders’ indifference to these problems. Their complacent self-deception made them avoid unpleasant questions – an attitude which, incidentally, complied entirely with the European code of behaviour in the Victorian era.

To this splendid indifference the Hungarians added their own brand of ‘patriotic isolationism." Not having any influence on the foreign policy of the Monarchy, the Magyars practically ceased to be interested in the important events outside their frontiers. The false adage: "Extra Hungarian non est vita." ("Outside Hungary there is no life…") became the motto of the conceited leadership of this apparently prosperous nation. No wonder that the rest of the world ignored the real Hungary. The image of the Magyar – a mixture of a Gypsy and a Hussar – with his fateful penchant for wine, women and song, was spread by globetrotting, free-spending aristocrats, operetta-composers and prodigal noblemen of the Budapest cafes.

Yet there was a credit side too: the cumulative achievements of the many talented, industrious and inconspicuous creators among the day-dreamers. In spite of the difficulties and indifference, national culture, economy and technology were enriched to an unbelievable extent even though the casual observer rarely noticed real progress behind the ostentatious glamour of Budapest.

The progressive Minister of Education, Jozsef Eotvos, introduced the 1868 Education Law which made schooling compulsory for all children to the age of 12. Only several years later did England and France introduce similar laws. Five universities, many colleges and countless secondary and primary schools were established. Opera houses, theatres, great public buildings were built in cities and towns.

The first underground railway system on the Continent was opened in Budapest in 1896. The country’s railway network was enlarged six-fold in fifty years, with several lines electrified.

By 1896 Budapest and the larger towns had complete sewerage: water, electricity, gas and public transport systems.

Around 1905 Austrian opposition to Hungarian industry weakened and secondary industries experienced a rather belated prosperity. Electricity became the main power-source. Industries connected with agriculture (milling, sugar-refining etc.) developed by leaps and bounds.

Science and technology, though handicapped by the depressed conditions of manufacturing industry in the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries, produced such eminent scientists as the two Bolyais: Farkas (1775-1856) and his son, Janos (1802-1860), remembered for their contributions to the theory of integral calculus and. absolute geometry respectively. Lorand Eotvos enriched Physics and Geology with several inventions, such as the torsion pendulum used in gravity measurements.

Technological inventions were more difficult to test, manufacture and market during these two centuries. Thus Janos Irinyi, a student of chemistry, made the first phosphorus match in 1836 but sold it to a manufacturer for a pittance. Anyos Jedlik constructed the world’s first electro-magnetic motor in 1828 (long before Siemens) but he had neither the m9ney nor the ambition to patent it (he was a Benedictine monk)

The obstetric physician, Ignac Semmelweis (1818-1865) discovered – years before Pasteur – bacterial infection, the cause of puerperal fever.

At the end of the century, the sudden upsurge in industry helped to create a number of useful inventions, such as the phase-alternating electric locomotive of Kalman Kando and the petrol carburettor invented by D. Banki and J. Csonka. Tivadar Puskas developed the principle of telephone exchange and invented an interesting predecessor to radio broadcasting, called the telephonograph.

The "Jewish question"

This sudden economic growth caused certain intrinsic problems. The Magyar middle-classes were neither willing nor prepared to participate in industrial and commercial activities. Their place was taken, in many instances, by newcomers, mainly Jewish immigrants. Hungarian hospitality had welcomed refugee Jews ever since the Middle Ages. These early immigrants had adapted themselves to the Hungarian civilisation and way of life and had become well-integrated citizens of the country. Jews took an active and loyal part in Hungarian freedom struggles, especially during the 1848-49 war. Now however, a large number of Jewish refugees began to flee from Russia through the Austrian province of Galicia to Hungary. In little more than a century their numbers in Hungary increased twelve-fold: in 1910 Jews represented 5% of the total populafion (1 million). These recent arrivals, speaking a tongue foreign to everybody in Hungary (Jiddish), and preserving their unusual eastern mode of living, rituals and ghetto-born secretiveness, constituted a homogeneous ethnic group unwilling and unable to assimilate.

For the first time in history the Hungarians felt antagonistic to the Jews, especially when they noted that the newcomers were taking over finance, commerce and the free professions (medicine, journalism). The expressions of this antagonism –though only verbal – angered the young Jewish intelligentsia, which reacted by seeking satisfaction in radical and revolutionary activities, especially toward the end of the War years, while avoiding military service or finding secure employment behind the lines. The leaders of the Marxist-Communist movements at the end of the War (1919) were almost exclusively Jewish.

| Timeless Nation |