| Timeless Nation |

26. AUSTRIA’S WAR – HUNGARY’S DEFEAT

(Hungary’s history from 1914 to 1930)

The beginning of World War I

The Austrian government made it clear that it intended to take stern measures against Serbia for fomenting Francis Ferdinand’s assassination. At the Crown Council, Tisza, the Hungarian Prime Minister, desperately protested against any measures which might lead to war, but the joint Foreign Minister and the Chief of Staff (both Austrians) insisted on armed retaliation. In vain did Tisza point to the danger of Russian intervention: the Austrian militarists managed to sway the old Emperor, Francis Joseph, who had, in the meantime, received reassurances from Germany’s bellicose emperor, William II.

The ultimatum expired and, as expected, Serbia refused to comply. On July 28, 1914, Francis Joseph declared war on Serbia. The reader will be familiar with the chain of events set off by this declaration: by August 3 most of Europe was engaged in the War.

The Budapest Parliament took a typically Magyar attitude. Before the declaration of war the entire Parliament had supported Tisza’s efforts to avoid the war. Now, all parties, including the Social Democrats and Mihaly Ka’rolyi’s Liberal dissidents, agreed to a political truce to enable Tisza’s government to support the war effort – which Tisza did, against his own convictions. The Hungarians’ quixotic code of honour demands absolute loyalty to the nation’s commitments, however unpalatable. Political realism and expediency are unknown words in the Magyar language. For four years the Magyar soldiers and their combat officers fought with dutiful courage on foreign soil mostly under foreign generals for an empire that was not theirs, in a senseless war to avenge the death of the man who had hated Hungarians. 3.8 million Hungarians served in the armed forces of the Monarchy. No Hungarian unit deserted, no factory sabotaged the war effort till the final collapse. Hungarian troops suffered very heavy losses : 660,000 dead and 750,000 wounded. The high command of the Monarchy was led by Austrian and Czech generals. There were no Hungarians in high positions on the General Staff and the highest position held by a Hungarian officer was that of a corps commander (General Szurmay, the able defender of the Eastern Carpathians). It is therefore pointless to revise the conduct of the war in which Hungarians had the subordinate role of providing the fighting troops. History books delight in listing examples of the muddled thinking and wasteful strategy of the archaic Austrian leadership.

The tragic role of the Magyar soldier is illustrated by the so-called "Limanova charge" in 1914, The Austrian commander sent Magyar hussars in a "foot charge by hussars against the Russian trenches defended by barbed wire and machine-guns. The charge of this "light brigade" (ten times the size of the famous Balaclava brigade) must have been a magnificent sight: resplendent in their blue-red–white uniforms (ideal targets for the machine-guns), armed with nothing but sabres – they were a sight to gladden the heart of their proud general (who watched the charge from the proverbial hill). The charge was a success: the general was praised and the hussars received countless decorations – most of them posthumously .

Italy entered the war against the Monarchy in 1915. Rumania, promised Transylvania and adjoining regions by the Western Allies, attacked Hungary in August 1916. For a while the Rumanian armies made some progress in Transylvania, which was defended by village policemen and the autumn rains. A few weeks later the German general Falkenhayn with hastily collected German-Hungarian troops chased the Rumanians out of Transylvania, then, in two months captured Bucharest and annihilated the Rumanian army.

On November 21, 1916, emperor-king Francis Joseph died after a reign of 68 years.

The reign of Charles IV

On December 30, 1916, Hungary’s last King and Queen were crowned in the historic cathedral of Our Lady in Buda. After the long, solemn ceremony (somewhat reminiscent of the ordination of a Catholic priest), the young king mounted his horse and rode up a man-made hillock built of the soil collected from the 73 counties of Hungary. There, with Saint Stephen’s heavy crown swaying precariously on his head, Charles IV made four symbolic strokes with Saint Stephen’s sword in the four wind directions, swearing to defend Hungary against all enemies.

At first glance, the position of the Monarchy seemed unassailable at the end of 1916: Rumania and Serbia were crushed, the Russian and Italian fronts securely held. But Charles IV was an intelligent man and he knew that the empire’s war potential was exhausted. He also knew that the nationalities were preparing to destroy the Monarchy. On his initiative, the Central Powers (Germany, the Monarchy, Bulgaria and Turkey) sent the Allied (Entente) powers a detailed peace offer in December 1916, suggesting the restoration of the 1914 status quo. The Entente rejected the offer, insisting on the "liberation of the Slav and Rumanian minorities". This rejection (costing another two years of war and another ten million dead) was the result of the successful propaganda campaign conducted by Czech intellectuals (Masaryk, Benes) and their Rumanian, Serb and other emigre’ colleagues in France and Britain. They managed to convince the Western Allies that the creation of Slav and Rumanian national states would stop German and Russian expansion in Central Europe. Tisza pointed out to the U.S. Ambassador that the breaking up of the Monarchy would result in the creation of several weak, multi-national states unable to resist imperialist pressure. (We know today who was right…)

Ater hearing Tisza’s arguments, the British (on American advice) suggested new negotiations with Austria–Hungary but the joint foreign minister of the Monarchy (count Czernin – of Czech nationality) broke off the negotiations, claiming that it would be disloyal to negotiate without Germany.

The effects of the entry of the U.S. into the War against the Central Powers were temporarily offset by Russia’s collapse and an offensive against Italy which was so successful that it took a considerable amount of bungling on the part of the Austrian generals to save the Italians.

In the Hungarian Parliament, count Mihaly Karolyi, now leader of the opposition, harassed the government, demanding radical electoral and other reforms. In May 1917 Tisza resigned. His two successors, count M. Eszterhazy and S. Wekerle, were unable to contain the opposition, the growing profiteering and increasing unrest at home. Still the frontline was holding everywhere, thanks mainly to the millions of hardy Magyar peasant soldiers. Russia and Rumania signed Peace Treaties in 1918 –but the impact of the American intervention was already felt and the total economic exhaustion of all the Central Powers had already decided the fate of the War. In September 1918 the Bulgarians collapsed and soon the Turks asked for an armistice.

In November 1918 the Monarchy signed an armistice with the Allied Powers in Padova, Italy. The terms of the agreement left the national frontiers untouched and directed the troops to return to their respective countries with their arms, under their officers.

The Monarchy soon ceased to be a federal structure: the various nationalities declared their autonomy and constituted National Councils. On Wekerle’s resignation, Karolyi, emulating the nationalities, formed a Hungarian National Council (quite needlessly: Hungary had her own constitution and government) and on October 31, helped by the so–called "Military Councils" (composed mainly of deserters), took over the capital, Budapest. The coup was bloodless (and senseless) – but a commando of the "Military Council" assassinated Tisza, who lived in a Budapest suburb.

The King, after some hesitation, appointed Karolyi Prime Minister.

Karolyi and the Republic

On being appointed Prime Minister, Karolyi commenced a feverish activity as the virtual ruler of the country. As the troops were returning from the fronts – with their equipment and under their officers, as directed by the Padova armistice –Karolyi’s government ordered the soldiers to lay down their arms and disperse: "Never again do I want to see another soldier. . ." said the Defence Minister, Bela Linder. Karolyi and his government naively believed that a "pacifist" Hungary would be regarded as the "friend of the Entente". Then Karolyi decided to "improve" on the Padova armistice and led a delegation to Belgrade, the headquarters of the southern Allied Forces. (This fateful pilgrimage had been suggested to Karolyi by one of his Czech friends. . .) The French commander, general Franchet d’Esperey, treated Karolyi and his deputation with utter contempt. On finding out why he came (uninvited) and on learning that Karolyi had dispersed the Hungarian armed forces, d’Esperey consulted his Rumanian and Serbian liaison officers and handed Karolyi extremely harsh instructions, including the immediate cession of large territories demanded by the Rumanians and Serbs. As it turned out later, the French commander had neither the desire, nor the authority to conclude an armistice with Karolyi and he made up his instructions on the spur of the moment.

Karolyi’s first fateful decision, the disarmament of the returning Hungarian troops, had far–reaching consequences. In November, 1918, no enemy soldier stood on Hungarian soil. The Hungarian units on the various fronts were well–disciplined, armed and in reasonably good spirits. They were willing and able to defend the Hungarian frontiers against the invaders whom they had either recently defeated (Serbs, Rumanians) or who had only makeshift units made up of deserters and ex-prisoners of war (Czechs).

On November 13, King Charles IV withdrew from the direction of the affairs of the State". Karolyi interpreted this as the King’s resignation and had the Republic of Hungary declared by the Parliament. The nation was now facing the fifth winter of the war. Rumanian, Czech and Serb troops moved into the undefended land, hundreds of thousands of refugees fled towards the centre of the country, the food, accommodation and fuel situation was catastrophic and the (Spanish) influenza killed thousands. The Karolyi government limited itself to promises of radical electoral and land-reforms and free welfare services – without doing anything. Disappointed, his former middle–class and moderate supporters left Karolyi and in January only the Socialists and Radicals supported him.

For more than two months the country had been without a head of State. Then in January 1919 Karolyi was elected President of the Hungarian Republic. By that time however, a new force was ready to fill the political vacuum created by Karolyi’s paralysed government.

Bela Kun's "Council Republic" ("Soviet Republic")

There had been no Communist Party in Hungary before November 1918. During the War some Hungarian prisoners of war had joined the Soviet (Bolshevik) Communist Party in Russia and were trained to prepare a Communist revolution in Central Europe. In November 1918 a group of these trained agitators, led by Bela Kun, were sent to Budapest and founded there the "Hungarian Communist Party".

The Social Democrats and the workers of the Trade Unions resented the Russian–financed activities of the Communists and bloody clashes soon occurred between the Budapest workers and Kun’s terrorist detachments (such as the "Lenin Boys"). Eventually even Karolyi’s meek government had to arrest some Communist agitators (including Kun)

In the meantime the Paris Peace Conference was in session, making decisions without consulting the defeated nations. In February, 1919, the Budapest Allied Commission demanded the evacuation of about three-fourths of Hungary in favour of Czechoslovakia, Rumania and Serbia. Karolyi, who now realised the folly of his "pro–Entente" and "pacifist" policies, resigned in March, 1919, handing over the supreme authority to the "Proletariat of the Nation".

The left–wing Social Democrats (the only active political group) promptly handed over the power to Kun and his fellow Communists. On the 21st of March, 1919, the Hungarian Council Republic was formed, governed by the Communists and some Social Democrats. Misnamed "Dictatorship of the Proletariat", Bela Kun’s regime lacked the support of most of the city proletariat and certainly of the entire agrarian proletariat: in fact it lacked the support of all classes or established parties. Its ideological basis, "Bolshevik Communism", manifested itself by little more than parrot-like repetitions of Russian– Bolshevik terminology in the service of the self–preservation of a group of unscrupulous adventurers. The organisers and supporters of the regime were people whose mentality was foreign to Hungary’s political, social and cultural atmosphere. Of the 45 "Commissars" (Ministers) 32 were unassimilated Galicians (cf. Chapter 22). Most of the urban workers and Trade Unions refused to co–operate with them or seceded from the "coalition". The peasants (the largest, most oppressed class) were not represented in the government. Neither were the middle classes (let alone the upper classes) nor any politician with appreciable Parliamentary experience.

The regime was maintained by ruthless terror exercised by the "Soldiers’ Councils" or other armed commandos, consisting of criminals, deserters, ex–prisoners of war and vagrants and led by sadists, such as the Commissar Tibor Szamuelly. This method of control was called the "Red Terror" by the Communists themselves.

The administration of the country (or what was left of it) was left to the town and village "Councils" which held absolute legislative, executive and judiciary powers (including the power to impose capital punishment for "anti-revolutionary" activities). These Councils were staffed by "reliable" city Communists. The estates were nationalised, not distributed to the peasants but administered by "Farmers’ Councils" (of reliable city Communists). Businesses and factories were similarly "socialised" (managed by reliable Communists). As a result, industrial and agricultural production practically ceased; the peasants refused to feed the "city scoundrels". Brutal requisitions evoked resistance, often in the form of sizable uprisings, which, in turn, were followed by the brutal retaliations of the terror gangs.

Kun recruited a "Red Army" to hold back the approaching Czech and Rumanian troops which threatened the existence of the Communist regime. The "Red Army", led by some able officers of the former Hungarian Army willing to defend their country under any circumstances, regained considerable territory from the Czechs in the north but was then ordered by the Allied Powers to withdraw. Thus the Rumanians could move toward Budapest practically unopposed. On learning this, Kun and his "government" fled from Budapest (July 31).

Rumanian occupation – national government

The Rumanians entered the undefended capital and began to loot and impose their own type of terror upon the much– suffering population. Various moderates tried to form governments but they were unacceptable to the Allied Commission. The only hope of the nation was now the "Counter-Revolutionary Government" set up in the south of the country, but not yet officially acknowledged by the Allies. This government– in–exile had recruited a small "National Army", commanded by Admiral Miklos Horthy, which was however not allowed to proceed to Budapest where the Rumanians were "absorbing" western civilisation at an alarming rate. After months of negotiations, the Rumanians were induced to leave Budapest and Horthy’s "National Army" entered the capital in November 1919. A caretaker government was formed and in January 1920 elections were held under Allied supervision. As a result, a moderate rightist government was elected. As the Entente forbade the restoration of the Habsburg dynasty, the Hungarian throne was declared vacant and Admiral Horthy was elected Regent (March 1920).

Following the collapse of the Kun regime (July 1919) Hungary had practically no law–enforcing agencies – these (gendarmerie, police, courts) had all been abolished by the Communists. Between July and November 1919 there were isolated, individual acts of revenge against those held responsible for the sufferings of the preceding months. There were also outbursts of anti–Semitic (or rather anti–Galician) feelings, as the most hated of the Bolshevik leaders (Kun, Szamuelly, Korvin) were Jews. This was the much publicised "White Terror": a series of regrettable, lawless acts, evoked by the "Red Terror" and made possible by the legal vacuum created by Kun and his regime.

The well–disciplined units of the National Army restored law and order and put an end to these excesses. Thus Admiral Horthy, whose name had been maliciously connected with the "White Terror", was, as commander of the National Army and then Head of State, the very person to stop these regrettable acts of revenge.

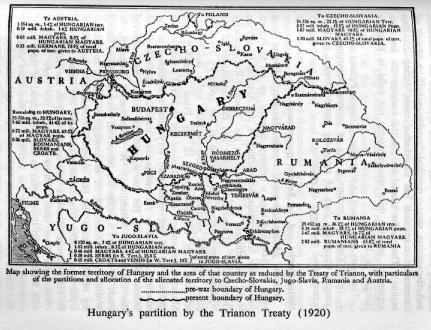

The Trianon Treaty

The verdict of the Peace Treaty was given solely on the submissions of the Czech, Rumanian and Serb delegations. Neither the Hungarian submissions nor President Wilson’s much vaunted 14 Points were taken into consideration. Hungary was punished more severely than any other country: she lost 71 .4% of her territory and 63.5% of her population; she was also ordered to pay reparations (in addition to the loot taken by’ the Rumanians) and to reduce her armed forces to 35,000 without heavy armament or national service. The country lost all her salt, iron, silver and gold mines and most of her timber and coal production. One-third of all Magyars were transferred to a foreign country.

The arguments against Hungary were basically the following: Hungary had started the War, she had oppressed her minorities and the country was a potential "trouble-maker", a source of, Communist corruption (an observation made during the Kun regime). The reader should be able to evaluate the first two arguments, and the third was obviously not valid in Horthy’s Hungary in 1920.

The treaty was signed at Versailles (Trianon Palace) on June 4, 1920; This day became a day of national mourning in a country where the days of mourning seemed always to have outnumbered the days of rejoicing.

Miklos Horthy and the Bethlen government

Admiral Miklos (Nicholas) Horthy, Hungary’s Regent from 1920 to 1944, had been a military diplomat, an aid to Francis Joseph, the last commander-in-chief of the Austrian-Hungarian Navy, the Minister for Defence in the "Counter–Revolutionary Government" in southern Hungary and the commander of the National Army before his election as the country’s Head of State. After his election he withdrew from active politics and left the tasks of government to his Prime Ministers and Ministers, becoming a dignified, aloof but respected constitutional monarch in all but name with very little interference in the country’s internal or external politics until the outbreak of the Second World War. He was scrupulously honest and observed the Constitution meticulously. A warm–hearted humanist, he made his country a refuge for persecuted Jews and Poles during World War II. Knowingly or unknowingly he started an interesting social evolution: he had himself surrounded by non-aristocratic personalities (the aristocrats treated him rather coolly). Of his 14 Prime Ministers only one came from the rich, aristocratic land-owner class. Horthy provided this "new nobility" with honours and titles (such as the knighthood of the "Vitez" awarded for outstanding war service) – somewhat similar to the British system of titles, honours and knighthoods (he was a great admirer of the British). Thus he gradually created a new, non-aristocratic, leading class of Hungary.

After the 1920 elections the Christian and Smallholder parties formed a coalition government. After the signing of the Trianon Treaty, Horthy appointed count Pal Teleki Prime Minister (1920– 1921). Teleki, scion of an historic Transylvanian family, was a world-renowned professor of Geography, an honest and wise statesman and a devout Catholic. He was an unusual politician in that his bluff sincerity, monosyllabic oratory and bespectacled, schoolmasterly figure clashed with the Renaissance decor and Baroque atmosphere of the Hungarian Parliament.

In 1921 King Charles attempted twice to reclaim his Hungarian throne. On the first occasion Horthy convinced him that his restoration – though welcome in Hungary – was against the stipulations of the Peace Treaty. On the second occasion, armed confrontation occurred between Hungarian troops loyal to Charles and those loyal to Horthy, while the Czechs and Rumanians mobilised threatening armed intervention if Hungary restored the Habsburg dynasty. In order to avoid further bloodshed and foreign intervention, Charles surrendered.

The Entente Powers exiled Charles to Madeira in the Atlantic where he died in 1922. It was one of the many ironies of Hungarian history that this pious, honest and humane man, with outstanding intellectual and moral qualities, loved and respected by all Hungarians, was not allowed to remain on the Hungarian throne – he was the first Habsburg who would have been welcome to it.

Teleki resigned and Horthy appointed count Istvan Bethlen Prime Minister (1921–1931). This able politician, scion of another historic Transylvanian family, was an excellent choice. His first task was to re–establish some measure of financial stability. In 1922 Hungary was admitted to the League of Nations. After three years of strenuous negotiations Bethlen managed to secure a substantial loan through the League for Hungary. (Foreign aid freely given to "developing" countries did not exist in those days). Interestingly enough, the greatest obstacle was created by the Hungarian emigres, led by Karolyi in Britain, who did everything to discredit Hungary and have the loan withheld from a country ruled by "Horthy’s reactionaries". Finally the loan was granted and Bethlen could stop the crippling inflation by introducing a new stable currency based on gold (1927).

An industrial prosperity of some sort began:a fourfold increase in manufacturing output brought relative affluence to the urban workers who also enjoyed progressive social and free health benefits.

The government was, however, unable to solve the agrarian question: 3 million peasants (more than one-third of the country’s population) lived more or less on subsistence farms of their own or as landless agricultural workers. The succession states carried out their much–vaunted agrarian reforms through the inexpensive device of confiscating former Hungarian landholdings. Hungary had no ex-enemy loot to divide – the land to be given to the peasants had to be bought from the owners. The Hungarians’ scrupulous respect for proprietary rights prevented them from confiscating even the huge estates of the Habsburg family (confiscated everywhere else).

In 1921 the government commenced an agrarian programme involving about one million acres (6% of the country’s arable land) distributed among 400,000 landless peasants. There is no doubt that much more should have been done to hand back to the Magyar peasants the soil for which a million of them died in two world wars.

Education progressed rapidly: eight thousand new primary schools, many high schools and universities were built during the ten years of the Bethlen government – not a bad record for an impoverished nation of 8 million. The electoral policy’ of the government was rather conservative: limitations of age, sex, residence, education and family status reduced the number of electors to about two–thirds of the adult population. The Parliament consisted of a Lower House (elected by secret ballot in towns and open voting in the rural areas) and an Upper House with its hereditary or appointed members and representatives of professions (similar to the House of Lords). The Regent appointed or dismissed the Prime Minister who did not have to be a member of the Parliament, but had to be supported by the majority party. The Prime Minister chose his ministers (not necessarily from members of the Parliament).

Law and order were maintained by a well disciplined and educated police and gendarmerie force (all commissioned officers were law graduates) and by well–qualified judges who meted out justice based on solid Roman Law as revised by the Code Napoleon and the Hungarian Articles of Law ("Corpus Juris"). In the public service bribery, embezzling and fraud were practically unknown but nepotism was rampant. The working classes – urban and agrarian – showed remarkable self-discipline and patriotism during the trying years of reconstruction, depression and second World War. Strikes and demonstrations were rare in the industrial centres and nonexistent in the country where the Magyar peasant continued to carry his thousand–year-old burden with enduring loyalty.

"Revisionisrn" and foreign policy

The idea that the Trianon frontiers needed a radical revision became the basic ideology in Hungarian politics as well as in education, art, literature and social life. The succession states and their protector, France, remained deaf to the Hungarian arguments for a peaceful revision of the frontiers (most Magyar– populated districts were contiguous to the Trianon frontier and their adjustment would have caused few demographic problems). The Hungarians reacted emotionally and the words "Nem, nem, soha!" ("No no, never!") rejecting the mutilation of the country became a national motto. Abroad, this propaganda, appealing to the heart rather than the mind, found a warm response in Italy; a somewhat amused acknowledgement in Britain and little success elsewhere.

The generations of young Hungarians brought up during these decades lived in the wishful dream-world of the "restoration of Hungary’s thousand-year-old frontiers". Though unattainable, this was a goal to strive for, to hope for, to struggle for and to demonstrate for. It was definitely a worthier cause to get excited about than some of today’s causes. To the nation, the lofty ideal of revisionism gave a sense of dignity and self– respect, lifting the people’s minds out of despair. On the other hand, this attitude certainly damaged the Hungarians’ chances of establishing useful economic ties with their neighbours and it also proved harmful to the Magyar minorities in the succession states. Hungary’s emotional (and ineffectjye) revisionism served as a pretext for the oppression of the Magyar minorities in Rumania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Moreover, in order to guard the results of their victory, these three states formed a strong military alliance (called tbe "Little Entente") with the sole aim of preventing Hungary from recovering her lost territories.

It had not occurred to a single Hungarian politician to pretend to accept the terms of the Treaty and thus ease the tension and the Magyar minorities’ plight.

The relations between Hungary and Austria were rather strained at the beginning of the period, as the Hungarians resented the fact that Austria had also accepted a slice of Hungarian territory under the Peace Treaty. France, the protector of the "Little Entente", maintained a hostile attitude toward Hungary during the entire period. The British did cast occasional, supercilious glances toward Central Europe, but the business of the Empire kept the British politicians from trying to counter-balance France’s influence there, though the Hungarians were eager to approach Britain. The first state to turn a friendly hand toward Hungary was Italy. A friendship pact with this country was Bethlen’s greates diplomatic success (1927).

By 1930 Horthy and Bethlen had achieved the seemingly impossible: the nation was back on its feet, the social and economic conditions were improving, the currency was stable and unemployment was minimal. Then, in 1931, the full force of the world financial crisis and depression hit the country's economy (still very much dependent on foreign trade, especially wheat exports)

Unwilling to lead the country through another crisis, Bethlen resigned in August 1931.

| Timeless Nation |